Inadequacy & the Flip Side of Why You Create

A series of phone calls I have had this week hearten me about humanity. A thought leader, a start-up co-founder, a memoirist, an herbalist professional, a novelist, a marketing boutique owner-cum-memoirist – they all reminded me of the importance of why.

But they also remind me of the flip side of why. And that positive flip side has more to do with the value of inadequacy than the need to feel good about ourselves.

The Why

The phone calls I had were with people writing books who had been selected for Discovery Sessions about their books and the possibility of their coming to the live author’s intensive Your Brave New Story.

“Imagine you’ve actually shaped and finished your book. That it’s at last out into the world. What does that mean to you? How will you be different?”

The responses took me aback.

One thought leader has patented an innovative solution to global warming. I’m not kidding. It’s good. And he has a potential good book and new story to tell. His motive? He told me didn’t actually care whether he got fame or not. He didn’t even care if someone else wrote the book.

When he thinks about what he’ll tell his grandkids he did with his time here, that’s what drives him.

Another person said that she thrives when she teaches, and if a captivating book that is part of the brave new story she’s about helps her teach more people, then that’s what drives her.

A novelist said it would be the culmination of her life purpose. The book and the new story she has to tell would be, in essence, part of her dharma.

I also had a complementary conversation with LeanPub co-founder Scott Patten.

We agreed that the joy of working with the people we do is that they’re not caught up in delusions of glory. They have great ideas and stories they want to share, and they deserve to know how they can shape a life and livelihood around doing that.

The Why of Pros

Cheryl Strayed didn’t set out to write her memoir Wild to visit Oprah’s home. She didn’t even set out to write about her relationship to her dead mother. She set out to make sense of a time in her life and ultimately to write a good story for readers.

The same could be said of Julie Metz and her New York Times best-selling memoir Perfection. “Oprah gives good hugs,” she told me, but that hug wasn’t her motive to write. She wrote to make meaning of an episode of her life and to write the best possible story she could.

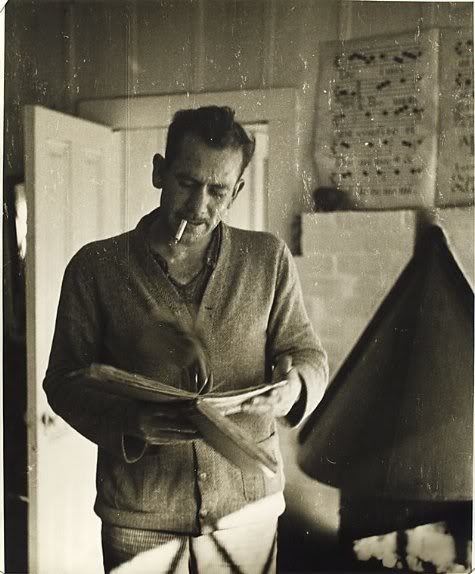

“If there is a magic in story writing, and I am convinced there is, no one has ever been able to reduce it to a recipe that can be passed from one person to another. The formula seems to lie solely in the aching urge of the writer to convey something he feels important to the reader. If the writer has that urge, he may sometimes, but by no means always, find the way to do it. You must perceive the excellence that makes a good story good or the errors that makes a bad story. For a bad story is only an ineffective story.” – John Steinbeck

There are some thought leaders who deliberately set out to write best-sellers. People like Jonah Berger study the models, break down the Bestseller code, and do the hard work that doing so entails. (Berger succeeded, by the way, in breaking the code, but he had the 10 years of research, the brain chops, and the writing chops to pull it off.)

A colleague told me recently of someone semi-renowned whose ambition as an author was to bring home the trophy. The trophy being a “bestseller.” Sometimes that drive works. Like 1 in 10,000.

Their drive is primarily about them, their glory, their name, their wealth. They can ironically forget the hard work and skill development necessary to earn a trophy.

Real winners, the ones I work with at least, let Right Intention drive them primarily. And what is that Right Intention?

Start with learning how to create something that will captivate and elevate a designated audience who cannot help but share your creation, and deep gratification is more likely to follow.

An Writer Versus an Author Driven By Why

We often write for ourselves, our own exploration of ideas and experiences and imaginings.

But in my experience authors assume the real task. They respond to the calling that their book draws them into. It could take a year. Or five. Ten.

An author knows she’s drafting to work things out for herself and that’s she’s ultimately crafting a book that is not for her. It’s for a world. More precisely, her patch of the planet.

An author knows she’s part of a bigger Story, a new Story potentially that her book is only a part of.

Self-Admiration, not Self-Esteem: The Flip Side of the Why

So when we know our why and when we want to respond to the calling of the author’s quest, we stop. We panic.

We say, “Maybe I’m not up for it. Maybe I want to hold onto my vision and not see the messy reality. Maybe I can’t really pull it off. Maybe I don’t have time. Or money for leisure and learning.”

Maybe.

But what I have heard this week is people – veteran and new authors – willing to face uncertainty. People admitting their vulnerability who in their thirties, forties, fifties – one 70 – willing to acknowledge they are hungry to learn, to test out, mess up, finesse, and try with intention.

Remarkable.

Maybe inadequacy is a doorway to learning. That’s the refreshing tenet of educators Terri Ellis and Chip Romer.

The drive to finish and send a book out there that matters is rarely driven by the author needing to feel good about himself. But it can result in building the author’s self-admiration.

Self-admiration – standing in wonder at one’s own excellent skillfulness – comes out of skillful learning. And that pursuit of mastery, as the work of Carol Dweck and others attests, leads to deeper gratification than simply seeking accolades.

The excellence that makes a good story good…

So, yes, maybe authoring a book is in part about you. But not the part of you that only needs a pat on the head (I do need those pats, too!). But the best in you. The potential in you that is cultivated with skillful means, alliances, practice, and wonder.

The potential that could deliver potent medicine via a Story that you and only you must tell.

Your skillful potential. That’s the flip side of your why.

DROP BY

At your marrow, what drives you to create what you do? Share your comments and perspectives below.

Oh wow, Jeffrey, this is a beautiful post! I particularly relate to the description of why Cheryl Strayed wrote Wild. Most of the stories that really touch me were created by people who were just trying to make sense of things, rather than make a killing. Books, blogs and movies alike. Not sure I’m ready to share my “why” (or the flip side) here yet, but maybe that’s A Life Delectable post to come. Thanks for your insight.